Q: It’s not every day that one contributes to a national action plan for endangered plants! Can you tell us a bit more about the program and your involvement?

The National Action Plan aims to highlight Australia’s most at-risk plants; understanding the species and the main threats faced by each. I was asked, on behalf of SMEC, to be involved due to my experience with one of the plants, Zieria exsul (banished stink bush), which is listed as ‘critically endangered’ under the Queensland Nature Conservation Act 1992.Zieria exsul has a highly restricted distribution on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast and is under threat from development.

My experience with this plant includes population surveys and the identification of a new population growing approximately 50km south of the only other known plants. I wrote a translocation management plan and was involved in translocating 12 individual plants, that were going to be impacted by a development, to nearby suitable habitat and propagating additional individuals to a new site to help ensure the species’ survival in the wild. The propagation program has been very successful, with over 50 plants propagated so far.

We are still in the early stages of the program and as this is the first time we’ve attempted to translocate the species, we are learning a lot about how these plants react to translocation and propagation. Ultimately, we will gain a better understanding of the species and the actions needed to preserve them.

Q: How does this lead to a better understanding of Australia’s most endangered plant species, and biodiversity protection in general?

Our understanding of many of these species is very limited, so this is helping us to understand how we can best protect them. For example, we may learn that a certain species responds really well to propagation but only moderately well to translocation – this is vital in understanding how the species can be established and thrive in an environmental offset site.

Through population surveys, we gain an understanding of what habitat types certain species prefer, including the soil conditions the species is associated with. This knowledge guides the identification of suitable habitat and suitable offset sites, improving the chance of a positive translocation.

Q: As an environmental scientist, how do you and your team ensure environmental practices are integrated into infrastructure projects?

A key aspect of our role as environmental scientists is to keep every stakeholder on a project informed of the environmental aspects relevant to the project, and to identify any associated risks early in the project. Early identification of environmental risks is crucial because it is much easier to incorporate environmentally sensitive designs from the beginning of a project and it helps to minimise complications later in the design process.

Q: Over the span of your career, you have been involved with diverse infrastructure projects in Australia, including multiple stages of the Bruce Highway Upgrade and the Hells Gates Dam and Irrigation Scheme – what is a stand-out aspect of your involvement on these projects?

Major projects are always a highlight – there are so many challenging aspects to overcome to deliver an optimal outcome. Personally, I really enjoy being part of a project where a tangible environmental outcome is achieved, for example offsetting koala habitat trees, planting and translocating threatened plants, or conserving threatened frog habitat. Re-visiting the conserved frog habitat once the development is completed, and seeing that the threatened frogs are still there, is an incredibly satisfying achievement. With the multiple stages of the Bruce Highway upgrade, a significant achievement is tailoring the mitigation strategies to the risks and impacts specific to each section. This has included the incorporation of a fauna rope bridge near Caboolture, and koala offset sites near Cooroy.

Excellent collaboration between the client, government agencies and our experts is vital to achieving these environmental and sustainable outcomes. It is essential, especially on major projects, that we deliver a solution that satisfies the State or Commonwealth regulator and provides the best environmental outcome possible whilst supporting and collaborating with our client throughout the entire project lifecycle.

Q: What do you find are the core challenges in delivering and supporting environmentally resilient and sustainable infrastructure?

Challenging the status quo by incorporating environmental design solutions into projects can often be the biggest challenge – it can be difficult to assign a tangible valuation to environmental benefits. Community expectations around environmentally sensitive designs have improved a lot in the past few decades, but there is still the need to communicate and build an understanding of why plants, animals, or vegetation communities are worth saving. I endeavour to shape this understanding to support cost effective design solutions that benefit the project as well as the environment.

Q: What do you think the future of environmental engineering holds?

Environmental engineering is vital for our future. As our population grows and development continues, we need to protect and preserve biodiversity to keep our cities and regions green, sustainable and liveable.

Vital programs such as the National Action Plan for Australia’s Most Imperilled Plants will enable an understanding and advocacy for the survival of these species. As engineers and scientists, we need to be committed to developing and delivering quality environmental and social outcomes that balance the short-term needs of projects with the long-term needs of the environment. I enjoy working with a team of specialists across a range of sectors who collaborate to push environmental, social and economic project outcomes beyond ‘business as usual’.

1. https://soe.environment.gov.au/theme/biodiversity/topic/2016/importance-biodiversity

Related

insights

Australia’s land is ready for a revolution Part 1

Australia’s land is ready for a revolution Part 1

As American President John F. Kennedy once said, “Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or present are certain to miss the future.” This is especially pertinent in Australia when looking at how we use and redevelop our land.

Combined retaining wall solution stacks up

Combined retaining wall solution stacks up

Dr Kourosh Kianfar, Principal Geotechnics Engineer at SMEC, believes that innovation is often found in examining the conventional use of existing products to meet a challenge — a belief he has put into practice.

Designing tomorrow’s sustainable cities: Lanseria Smart City

Designing tomorrow’s sustainable cities: Lanseria Smart City

The Greater Lanseria Master Plan (GLMP) is the first stage in the development of the new Smart City in Lanseria (Gauteng Province), as announced by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in his 2020 State of the Nation Address. Following the announcement, a joint initiative led by the Gauteng Office of the Premier was formed to undertake extensive studies and engagements for the planning of Lanseria Smart City.

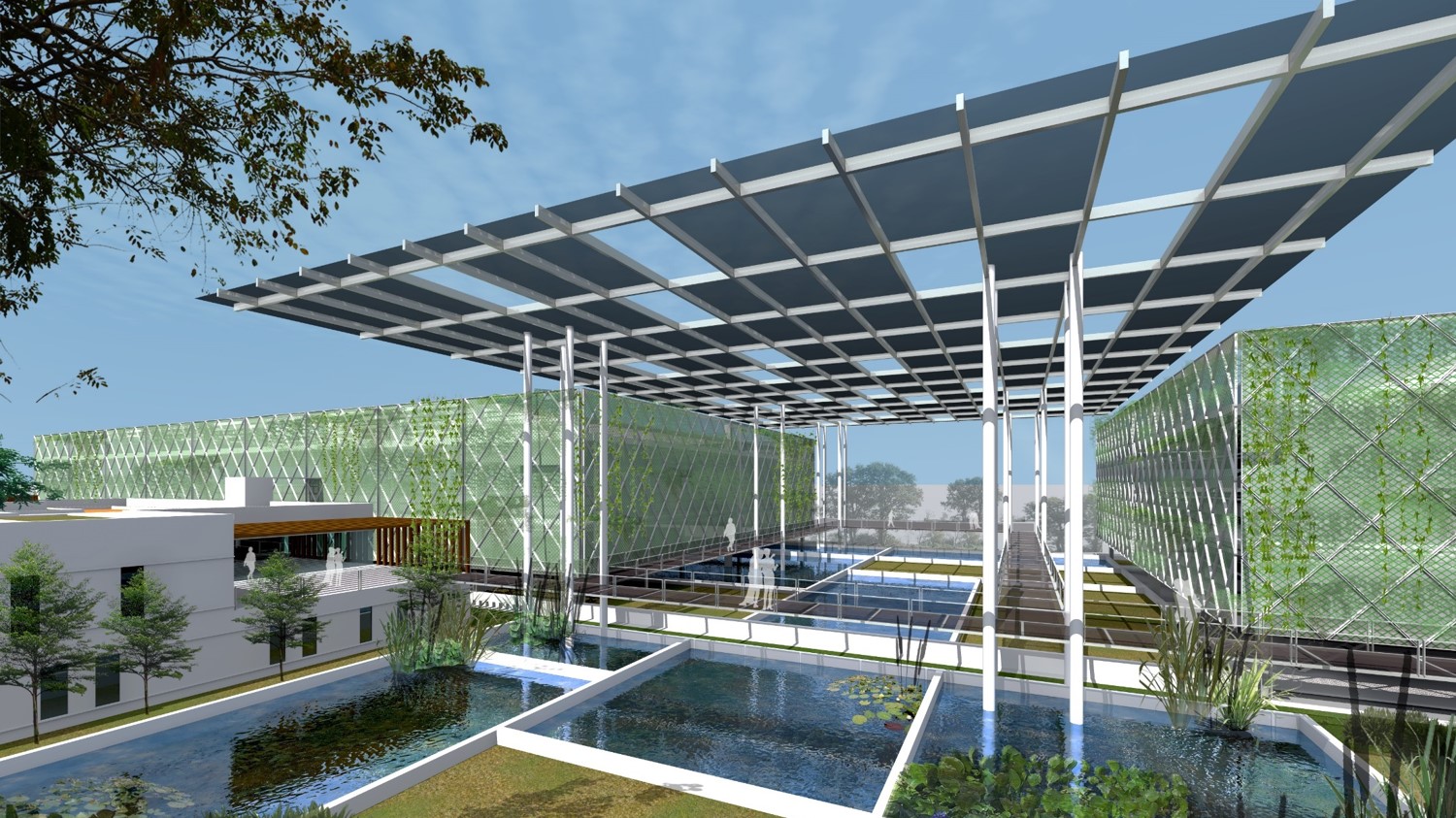

Floating ponds – urban fish farming to transform global food production

Floating ponds – urban fish farming to transform global food production

Over-fishing, poor management of fish stocks and the impact of a changing climate mean that we must now look increasingly for new ways of satisfying the global demand for fish as a sustainable source of food. The development of the Floating Ponds urban farm concept – a radical systems based design incorporating innovative engineering and technology – holds the potential to turn the dream of efficient, self-sustaining food production into a reality.